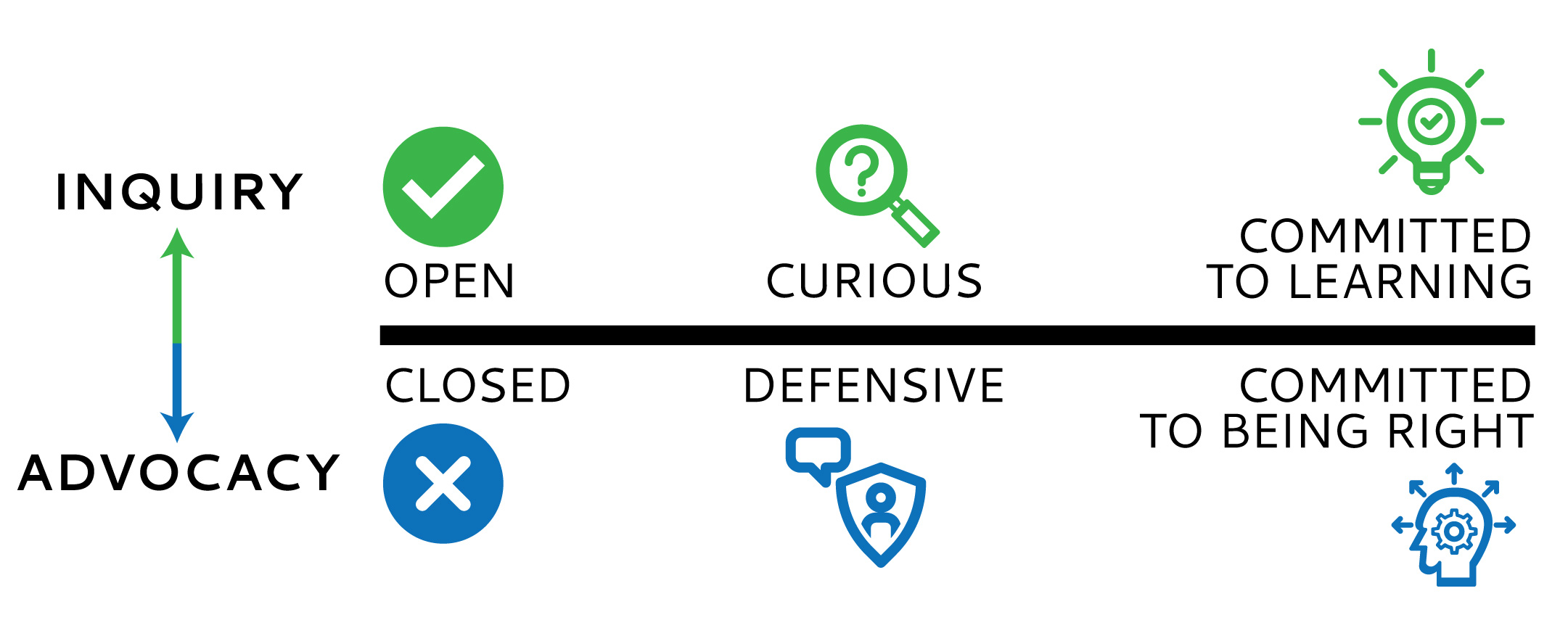

I can’t recall when or where I first saw this diagram, but I should, because it had an immediate and lasting effect on me. I do know it came toward the end of my years as an operating executive, which is a shame, because I missed out on the power of this simple visual to lift me out of those moments when I wasn’t being the best leader I could be. While I can’t pinpoint its origins, I found a similar concept in Carolyn Taylor’s 2005 book, “Walking the Talk: Building a Culture for Success.” Maybe it grew from there. Whatever its provenance, it’s a keeper:

There’s not much to unpack here: when you find yourself below the line, rise above it. Because when you’re open, curious, and committed to learning, you get better results. At work. In life. Inquiry eats advocacy for breakfast.

I’m not trying to give advocacy a bad name. It has its rightful place in fields as varied as jurisprudence, public policy, social services, patient care, and human rights. It has its place in business, too, if used judiciously. But as a modus operandi in the workplace, or at home for that matter, it’s counterproductive and leads to poorer outcomes.

I’ve never really been one for self-talk, but that changed after I came across this Jedi mind trick. Even the best of us find ourselves below the line with some regularity. But because of this mental Maginot Line, I’m now much more aware of it, and actively work in real-time to climb above the line when I find myself closed off to argument, being defensive, or fixed in my position.

“Think Like a Scientist”

I came across a deeply researched, even more potent expression of this concept when I read Adam Grant’s New York Times bestselling book, “Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don’t Know.” Even better, soon after its publication, I attended a conference at which he presented additional insights based on his research.

While not referenced in the book, Dr. Grant’s findings echo the philosophy of one of my boyhood heroes, UCLA’s legendary men’s basketball coach, John Wooden. He once said, “It’s what you learn after you know it all that counts.” Decades before analytics came to sports, Wooden embraced a data-driven approach to coaching. When his methods didn’t yield the results he was seeking, he changed them based on an analysis of the detailed notes he kept of every practice and game. He thought like a scientist, and in the process led UCLA to ten NCAA men’s basketball championships in a twelve-year span.

Grant urges us to do the same, to “think like a scientist”:

- Doubt what you know

- Be curious about what you don’t know

- Update your views based on new data

Here I’m reminded of John Maynard Keynes, the father of macroeconomics, who once said, “When the facts change, I change my mind; what do you do, sir?”

It’s not always easy to follow these simple instructions. After all, we’re human. To help, in addition to thinking like a scientist, Grant suggests two other aids:

Build a challenge network: a cadre of pleasantly disagreeable people who will not tell you what you want to hear. Importantly, people with whom you can have task conflict that doesn’t spill over into relationship conflict. Task conflict is constructive, relationship conflict the opposite.

Create psychological safety: an environment in which people can disagree with you utterly without fear. I spent my career constructing psychological safety zones, to which I owe in large part any success I may have had. The higher in the organization you are, the greater the fear factor, so the harder you have to work to gain people’s trust.

I still fail at times to apply the lessons taught in Taylor’s and Grant’s books. Just ask my wife, son, or closest friends. But I couldn’t have a better challenge network nor feel more psychologically safe with them. They’re the best science teachers anyone could have.

© 2023 S2P2, LLC. All rights reserved.